When Mr Jacob Met Prime Minister Nehru and Other Stories

On Village Maestro, new book by Varghese Mathai

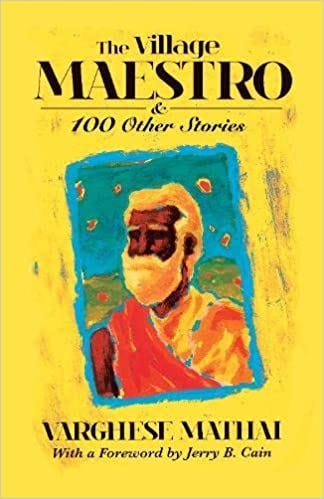

Varghese Mathai is the village maestro. His stories turn out to be Biblical, even when it is about Drona and Ekalavya, a story about the other side of the guru-shishya divide. Mathai’s stories in Village Maestro (Pippa Rann, Pages 292, Price Rs 599) are not lullabies, but wake-up calls for us to pause and ponder, learn and act, help and heal.

The essence of these 101 short, chewable stories are that however dark the night might be, there is sunshine to bask in, if you are willing to open your eyes and open yourself to the world. These are truly ennobling stories to which you can turn to for upliftment, solace and that much needed shot of courage.

I have read all these stories. I would rather call them illustrations of minds. In Tell Me Who I Am, in a mere hundred words, Mathai takes us from management consultants to Oedipus, to the nub of life—Know Thyself. He reminds us that the truth about ourselves is the hardest part of our knowledge search and management.

In Two Men and Their Widows, Mathai does what a good teacher ought to do—he sheds light into the darkness of a little understanding. Mathai reenacts the myth of Sisyphus in an astounding feat of spiritual leap, by bringing in John Bunyan, to leave us stunned at the progress. Mathai tells us that Marxist thinkers offer Sisyphus as the model of the suffering human. (It is the same in Dead Poets Society.) Sisyphus groans under his load while rolling the huge stone up the steep hill, so do all humans under harsh economic systems. We revolt against forced authority and seek to replace it. As Mathai sees it, some existentialist philosophers too chime in saying Sisyphus helps them show how humans can dare even gods, thus scorning their vengeful power.

That is then Mathai shows us the Pilgrim and his progress. Bunyan’s pilgrim too had a burden, one that had been bound on his back. He climbed in wearying pace to the top of the hill, where stood a cross. Mathai tells us that as soon as he came to the cross, his burden loosed itself and rolled down, right into the sepulcher, and it was seen no more. Bunyan’s journey’s end is in the Kingdom of Light, instead of in Pluto’s dark world, as Sisyphus does.

The thing is that the reader may not agree with the spiritual arc all the time. But when Mathai says that discerning the difference between your own selfish desires and God’s call is as important to your spiritual life as it is to the destiny of your loved ones and your nation, as well as to the world as a whole, it is difficult to disagree.

Mathai is a professor of English at Judson University in Elgin, Illinois, USA. A Malayali, Mathai completed his PhD at Baylor University in Texas. These stories took shape in his classrooms. These were his class openers. Mathai used to begin his classes with an unscripted narrative that took the shape of a parable or microstory. The matter came from an array of sources—history, literature, philosophy, science, religion, media events, etc.

One such astonishing story is about how a lay evangelist, Mr Jacob, presented a copy of the New Testament to Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, early one morning, describing himself as an ambassador. Ten days later, Nehru died.

Nehru used to set aside a weekly hour open to meet anyone who might have a reason to meet PM. It happened during a such an hour, but Mr Jacob was not aware about such practice when he did it.

That such an incident can take place today is hardly conceivable—how did a man of no personal clout meet with the prime minister at an hour of his own choosing? The mystery is, how did Mathai come to know about this incident. And This the only story in this collection that ends without a takeaway. All the other stories come with a bone. Chew them.